How to let go of one’s mother? How to let her die after the magnitude of years during which she was the boulder that our roots have clamped themselves over and around, absurdly daring follicles unwittingly holding her at the center of our being? Then converging beyond her, growing one solid trunk, spirit erect and driven, feeding from her still, no matter how high the reach towards heaven we dare, the very heavens where, ironically, our mothers will manage to precede us nonetheless, having slowly, subtly, insidiously extracted themselves from our grasp?

Our roots are like tendrils at first, seemingly unsubstantial even, started deep into the invisible mother earth; roots then pushing up, only to finally emerge somewhere on the earth, finding a surprisingly comforting, odd mass already set above us, anchor and shield all at once; roots twisting and winding progressively to encircle and entwine themselves to this massive rock rested on brown earth where it must have been known, through untranslatable generations of time, that we would come forth?

How then to envisage calmly the emptiness by which we will be filled from the absence of this all-encompassing presence? Missing a being essential to our own, a being at the source of our fibers, that yet wrenched itself out, blood of the heart, driven to dissipate in the infinite?

Is it true then that the dead wait for us on the other side?

Would you have guessed the complexity of my feelings for my mother if you had only read about them in my memoir, Unseen Worlds, where instances of life and words shared very different from these are described?

No?

Is all of truth then attainable in a memoir? It has been said that all fiction is autobiographical. Can it be said that all memoirs are a kind of fiction?

God’s face is hidden from us. And God is also said to be Truth. So, is truth, like God, hidden or unattainable because it is multifaceted, subtle, made of dreams, hopes, imagination, and a will to master the void? Is truth in a memoir unreachable as well, for the same reasons?

Undeniably, writing a memoir demands choices out of us. A central theme must be decided on, one that will give coherence to a vast array of experiences, our confused emotions about them, the numerous touch-and-go episodes we shared with a number of people, even if all of it turns out to be all at once both lasting and ephemeral.

A memoir also demands the courage to show oneself in public, body naked on the beach. But like in strip-tease, there is “strip” and there is “tease”—you choose what you will remove or leave on, how and when, under which light, which best angle showing—in fact, it is a public creation—a mixture of entertainment and installation art.

I grew up learning that God is the only one who knows the truth of the world, and about us. He sees through the screens we set up. He knows our thoughts. He knows the truth in our memoirs—He knows its intent towards greater truth or greater vanity.

Regardless of the possible purity of intent involved in its making, a memoir is a subjective presentation; subjectivity makes choices there; it is impossible to do otherwise. Human beings are already confused about their nature, origins, and destinations. How not to be? We are not static beings easily pinpointed; we constantly have to adapt to our evolving selves through the years, within a constantly evolving environment and world, and even if aging and the changes it brings are a good thing, because we see more, we understand better, we feel at deeper levels, we empathize more, we forgive and let go, even one’s mother.

The heart itself changes throughout; its truth evolves. We start with love, and then come the different stations: love before you can be hurt; hurt so you have something to transcend; transcend so you can be brought face to face with God. And when you see God’s face, you realize that you are back where you started.

If you only took your love for your mother as a model to examine these internal–ie emotional, psychological, spiritual—stations of personal evolution towards seeing God’s face, the stories you would write to bring to life that maternal relationship for your reader would vary from station to station.

Writing about oneself requires an ongoing selection process. This selection is affected by a multitude of unconscious factors: how old you are when you are trying to remember how young you were; what you can or are willing to say of what you see… in that selection process, truth itself becomes a shape-shifter. I am not saying that truth is falsified, I am saying that it is altered, amended, revised, refined, transformed, ie it is different. What has been kept out belongs to the whole truth, but only God is able to encompass the whole truth about us in the world, for now.

Faith can and will be derided. We guess at God’s existence, we feel Him partly, we recognize His manner, and we discern His interventions. Even whilst we argue the certainty of His existence because of these feelings, others will use the same to argue that we have invented God. It is also why they will say that there is no Truth, that all histories are told through the subjectivity of the narrator, the point of view chosen, and what the writer hoped to create or manipulate in the minds of others. As evidence to that is the history of the Christian Crusades written from the point of view of the crusaders or that of the Arabs. These contradictory histories have been written and they are indeed not the same tale. A recent movie, “Operation Finale,” tells about the capture of Nazi officer Adolph Eichman hiding in Argentina, and his subsequent trial in Israel; it was a beautiful effort towards understanding truth in each one of us, but Eichman’s ideas about the “what” and “why” of the Jewish Holocaust will never coincide with that of the Jewish people’s.

Our need for self-justification and self-protection will unfailingly push us to color and explain things to our advantage. It would be honest to admit that either memoir or biographies involve manipulation of the reader, even whilst they equally stem from an ultimate desire for the truth—understand what happened, remember the dead, and share what was learnt. Sigmund Freud said that an unanalyzed life is not worth living; a worthwhile suggestion, but one where he too reveals his own bias—the argument is to his advantage, since he was the inventor of psychoanalysis.

I have had my own experience of Freudian psychoanalysis. At the end of these five years, I was a different person than when I started. Had I written the story of my psychoanalysis, my perspective on it and the story I would have told of the relationship between my analyst and me would have been different had I wished to describe its beginning or its ending.

Perhaps the only true history, or memoir, are those that describe a process—the start of the adventure and the many stops taken to get to the end—the “when” and the “how” to the “where.” That is what I tried with Unseen Worlds.

I am even tempted to say that writing a memoir is like having one’s house blessed. I did that recently.

“What would you like this house to be blessed for?” the priesthood holder asked.

“I often hear from Mormons that our homes should be held as holy as our temples.” I said. “So, what I want is what Jesus wants. I want those people who wish me well to be the only ones allowed to enter my house. Only people who have pure intentions towards me and mine. I want my house to be a ‘hear no evil, see no evil, say no evil’ sanctuary.”

Well, my request probably excluded already half the world, and me with it. Our ongoing battle with the omnipresent presence of evil on earth is the trial we call Life. And we are all on trial, not just the Adolph Eichmans of this world. The bad news for Hitler is that suicide and death are not an escape from justice; real justice—divine justice that is.

Those who write a memoir put themselves on trial. The mind’s task is to present arguments for its prosecution and for its defense. However, the mind will not write them all down; it is clever. It will continually decide what evil or good, to hear, see, or tell. The mind’s bias, its potential towards “untruth,” is thereby established from the start. Whilst Satan is not able to enter God’s temple and house, he is able to infiltrate our minds, lives, and memoirs. He never stops trying to enter the temple or our hearts, this vulnerable edifice protected only by the frail strengths of our thoughts. God’s temple however, is protected by our combined intent, and His presence. Not all members of the Restored Church of Jesus Christ are allowed to enter. One’s purity of intent is formally questioned beforehand. Your word of honor is all that is required. If you lie, God will know—your fate is in your choices. It is believed that the purity of the mindset of people inside the temple creates a real, physical bloc. The intent of the people inside the temple, albeit flawed, unholy people striving for Christ-like perfection, is a filter powerful and sufficient enough. “Enough for what?” you might ask.

In writing a memoir, in a way, one also blesses one’s story as if a house or temple. The writer decides what will be allowed to enter. The memoir is declared holy ground. Intent is an effective filter there as well. My own memoir created its holy ground, and I performed in it my holy ordinances, inviting the past and its dead to be remembered and blessed.

Intent is indeed a filter, but not a falsifier. A half-truth is not a lie. A face half-revealed is not unreal or untrue. The part of God’s face that we intuit, or see, is not false because parts are withheld.

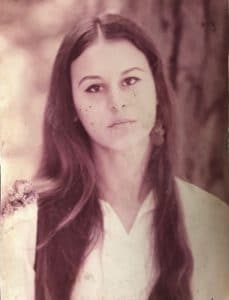

Christians are told that people are made in God’s image. Yet all of us on earth are people continually in the making, people in process, growing, transforming, changing physically and emotionally. The child I was is also the mature woman I am now. Two visibly different faces, two beings standing at opposite spectrums of time are yet the same. Our challenging truths stand and confront each other throughout time, different yet the same.

And if it is true that we are made in God’s image, can we then also infer that God too transforms? Is the God of the Old Testament the same forgiving one we love in the New Testament or in the Book of Mormon? Do we adapt to Him progressively, or does He modify Himself according to our level of maturity and goodness? Scriptures tell us that God discloses only the amount of knowledge that we are ready to handle. Can the same be said about memoirs?

Please look for my memoir Unseen Worlds on Amazon out now.