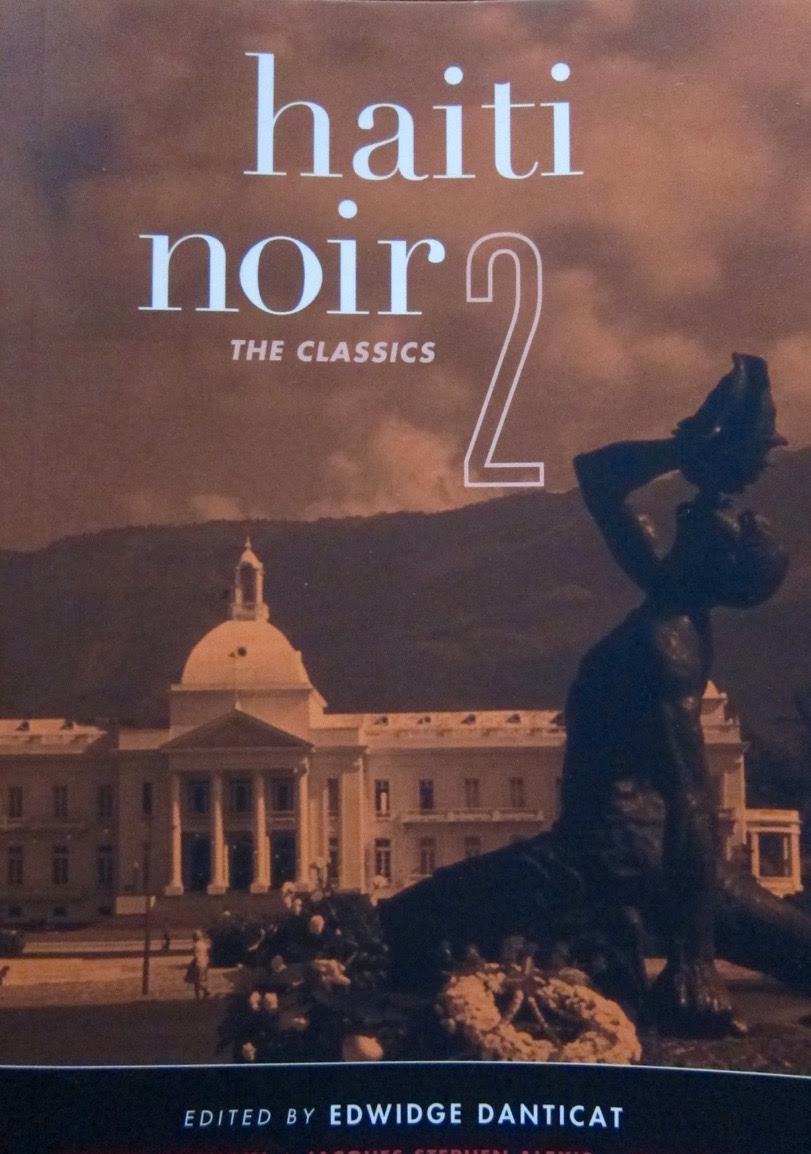

Marie-Ange’s Ginen

from The Company of Heaven: Stories from Haiti

My name is Marie-Ange Saint-Jacques and I got on that boat November third with my heart open and my eyes closed. My mother, Venante Saint-Jacques, also got on the boat. She too did this with an open heart since she got on that boat only because of me, but, unlike mine, her eyes were open—they had to, you see, because she had come to watch over me. So, that Sunday morning, she faced the ocean, dropped on her seventy-year-old knees, took the scarf off her head. It flapped softly like a flag in the early breeze before she could lay its white square flat on the gray sand of Balanye beach.

The others were startled when they saw her kneel, bare her head from its cotton-cloth protection, expose her white hair and the vulnerability of old age–offer it all, whatever its worth, whatever the cost, with such a simple gesture as that of pressing the white square into the sand, neatly and with both her bare hands as if to say: “This is all I have and take it—my head and all the images stored in it”. I knew more than they did, so I did not have to be startled and imagine what she’d be thinking. I knew her heart. What was going on in it at that moment would have sounded like “Take all that my head has kept safe all this while—take my father’s smile when he last saw me, take my mother putting cushions on her old chair to make me comfortable near her, take the trees, the friends, the old folks, the luster of leaves at the rainy season, my demanbre, my whole life, here! I am going up that boat because I know you are hungry—death is always hungry. More, give more! So here I am to feed you with my body—you can bite it, chew it, maul it, disperse it, erase it and erase all that my body ever meant to me or to anyone else, just so you don’t take Her standing behind me. Don’t take her! Change your plans, don’t take my baby, my daughter who sees no other way out of her misery than to sell that bit of land we had so she can pay our way onto this boat and jump into your mouth. Take my life and all the good I ever did and remember I served you well—this has real weight. Dismiss the bad—there is no power in the bad.”

They were startled and scared because they could see that she had no hope. She had no hope and that is why she was going up that boat. No hope for the boat’s fate, no hope for them, no hope for her daughter on that boat unless she came and bargained with death—traded herself. They knew too that she could have lit a candle. She hadn’t. She could have lit three, seven, nine, twenty-one candles! She hadn’t. She could have deposited flowers on that scarf. She hadn’t. She could have offered an egg, white flour, white rice, and even meat—chicken meat, goat meat, cow meat, any or all meat. She hadn’t. The simplicity of that white scarf bare of everything else besides itself was more powerful and frightening than if she had loaded it with gifts. These would have been palliatives. Straw men! They knew it. With the determination of complete abandon, she had reached for the double knot behind her head, untied it slowly as if she were thus undoing any resistance in her or any desire to live. She slid the scarf off her head as one exposes the ridiculous simplicity and flimsiness of the self, and laid it all down.

They waited for her to finish and she, the most hopeless, was the first one to get up the plank to the boat and lead the way to the journey at sea they had all paid so dearly to make. Each one of us here had paid our fare with all we had left that we could call our own. In some ways, we had also paid with the whole of our lives and of our parents’ lives before us because it took the slow unfolding of all these life stories in order for fate to have brought us to that point, that day, to go up that boat. What they saw my mother do was familiar. Disturbingly familiar–her desperate deal was understandable to their anxieties, to their cramping, empty stomachs, their restless sleep, their dying children, their dying lives. Everyone here had made the same desperate deal. But my mother had one less thing than anyone here had–hope for her own self. But the hope my mother had was that if all of us, the boat people of Balanye, if we were to be lost at sea and engulfed by the ocean, if fate had this in her plans that there’d only be one survivor, one survivor to make it alive to the land of promise—America—that it’d be me. No one smiled at what she was doing, no one smirked, and no one stepped on that scarf on their way up the boat. Each one skirted it carefully, paying it the kind of respect they wished death at least would give them, if life never did.

By the time we had all gotten into the boat, the tide had risen and reached for the scarf. The same Chenèl I grew up with and who sat on the deck most of the first day said the scarf followed us for a long while, undulating like the water’s surface until something below pulled it down abruptly. Chenèl says that, then, his heart sank with the scarf too—he didn’t know if what he had just seen meant the bargain old Venante made was accepted or if it was a symbol of the coming fate of the people of Balanye, all of us as one.