One may hear that “a picture is worth a thousand words”—I imagine that “pictures” also encompass photographs, drawings, images, posters, paintings, murals and the like.

But if we consider the “picture world” from either side of seeing or being seen, we realize that in many ways, we too are “pictures,” or “images,” albeit moving ones, viewed by another who faces us at any given moment of the day.

Looking at it in this light, I then propose that the way we present and conduct ourselves, the gestures we make, all become very significant—the way we move matters because every motion of ours is potentially worth a thousand words to the person watching.

But what about “the gift of tongues?” What is its value in contrast to “pictures being worth a thousand words” already? Is speech, or the use of words, in language or in writing, a self-indulgent power that we abuse too easily? Especially when words are not measured or weighed carefully in the manner of poets, or in much the same way that a painter might organize, compose and edit her or his work in progress?

And one might even playfully wonder if the Creator had a reason for situating our eyes made for images, our ears and mouths made for words, very closely to each other in the kind of “control panel” our faces might represent. Is there a message intended for us there? Are we to understand that the senses must work together for each to attain its full measure?

And if a picture is worth a thousand words, is it possible that a thousands words are worth a picture? What happens when you match picture and words together? Can words say what images cannot, and vice versa? Do they best work together, or do they best work separately because each is its own language aiming at different regions of our sensibility and brain?

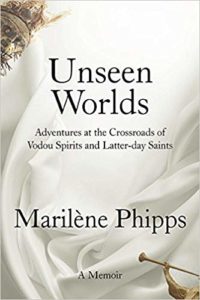

I’ll ask you this: What happens to your perception and understanding of image and text when I put this photo of my brother and me next to these related excerpts from my memoir, Unseen Worlds?

Ask yourself if a photo or a text direct, and thus limit, your experience of either? Or do they enrich it?

So look at this picture below in silence. And then read the text below it, an excerpt from the first chapter of Unseen Worlds.

“I was born in a tropical climate at a pre-dawn hour when it was still dark, but cocks crowed nonetheless. Forceps yanked out of my mother a ten-pound baby, bald, jaundiced, disoriented. Glaring light aggressed me, and I ached for the hydrous milieu from which I had just been ripped. The Bourand Maternity Clinic’s antiseptic, bare walls were the first to resound with my cries…

…I was a white baby in a country of black people; a Haitian baby girl produced by a French mother in a culture that prizes sons…

…My father entered the room with my two-year-old brother, Gaëtan, who trailed hesitantly behind him, unnoticed by nurses prepping me for the crib and for display to visitors…

…My brother was the first gentle moon I knew. He was our grandmother’s fifth grandchild, one endowed with a smile shaped like the melancholic crescents seen glowing in the night skies of Persian miniatures. The first time he leaned over my crib, wonder was established between us…

…My brother had the charm of birds. Song was his manner. He was a man in his full maturity, and when stretched on his deathbed at the Canapé Vert Hospital in Port-au-Prince, eyes aglow, he whispered a few words to me one night:

“You and I are twins.”

I spent my life judging him as being so detached that I found him coming short of being a proper brother, while in fact, I came to realize too late that I had close to me someone more necessary—a double. We were the twinned sides of the same golden coin. I began to discover that which had been imprinted on him as a gift—to successfully achieve my maturation. We were each other’s guides. I was to help him finish dying, while he was to help me finish living. He had seen it all along. I had not. His passing from life was dignified and discreet, but he took much of me with him then. I did not feel the tear at first. It made no sound.

“Where does it hurt?” his doctor asked him one morning during a routine visit at the hospital.

“In my soul,” my brother said.

He was willing to die, although he never stopped reveling in this island where he thought women as joyous as fruits. He commented on how it felt for him to live in a place where movements and sounds of the sweeper begin the day, rather than end it. It was not death he feared but being trapped inside the four walls of an unshakable room, unable to commune with the sky. He never could sleep in a bedroom, even the one decorated by his mother especially for him, with portraits of herself. All day at the hospital, he pushed away the sheet the nurse kept pulling back.

“It’s heavy to bear… this ailing man’s sheet…”

One would prefer that death occur like tropical rains—falling suddenly, with great bursts of thunder from a yellow sky, causing two children to run for cover and curl up together in a corner of their bedroom, a frightful delight burning in their eyes…”

Now, look at the photo again. Do you see it differently?

Please look for my memoir Unseen Worlds on Amazon. Out Now!